When discussing the works of the local renowned artist Chow Chun Fai, it is always accompanied by certain classic movie scenes or cityscapes with shared memories. His creations have always been authentic, ranging from oil paintings, photography, installations, etc., all revolving around local culture, the Hong Kong style, or even social issues.

Many people have fantasies about artists, thinking that behind the elegance of art, the creative process must be romantic. However, if we set aside the fragrant exhibition scene and return to the creative process itself, we will find that in Hong Kong, many art workers are based in industrial buildings, immersed in their creations. Without a quiet environment, amidst constant transportation and mechanical noise, these creators are quietly producing an intangible culture. Chow Chun-fai has been stationed in Fo Tan for 18 years, and it is absolutely true to say that he is a witness to the Fo Tan art scene. From the industrial area that was once only factories, slowly developing into today’s “Fo Tan Art Village,” the city’s appearance has been constantly changing, yet he continues to participate in the community through his creations.

Over the past 18 years, his identity has changed along with the city, transitioning from a taxi driver, full-time artist, representative of a pressure group (“Industrial Building Artists Concern Group”), to a candidate for the Legislative Council cultural sector. These seemingly unrelated identities have all been experienced by him. From a passive creator to an active participant in the system, he eventually returns to art. What drives him to step out of the circle of creation and participate in the community in another identity? Art and politics seem to be opposing forces of emotion and reason, indirect and direct. How does this contradiction affect his work?

In this episode of “Art City Travelogue,” we step into the creative base set up by Chow Chun-fai in Fotan Industrial Building, allowing us to see how he navigates the city with a diverse identity and discovers creative inspiration full of local consciousness.

“I didn’t intentionally set out to paint local elements, but through the lens documenting daily life, I discovered my life is so closely related to Hong Kong.”

Due to his family’s involvement in the taxi industry, Zhou Junhui was already a part-time taxi driver while still studying. Studying art in college, he had not yet formally entered the art scene, but had already interacted with many taxi veterans. At that time, creating art and driving a taxi went hand in hand, two completely unrelated activities became the focus of his life. Sending a creator to be a driver already sounds inappropriate, but being able to persist in this job for 8 years, we are all curious about what kind of experience this “identity misplacement” is for him.

Zhou Junhui also joked that he actually didn’t enjoy it at all, but his father was unwell at the time, so he had to take care of those two taxis for him. He described, “Taxis have a pretty Hong Kong rhythm, they shuttle through the city in a hurry, but at the same time, they are also a very lonely thing. When you drive at midnight, no one in the world knows where you have been.” But precisely because of the solitary time when driving, he found the pleasure of observing the city while navigating the streets and alleys, also deeply feeling the experience of surviving alone in the city. These subtle emotions unknowingly became the nourishment for his future creations.

Because of his close relationship with taxis at the time, Zhou Junhui smoothly incorporated them into his creative work, starting to paint all the scenes he saw in the car. As the city’s architecture and landscape continued to change, he documented aspects of Hong Kong life and the ever-changing urban scenery on the streets during that period. He said, “Initially, I just took my camera out and took pictures on the streets, purely wanting to paint with the lens’s images. But as I passed through the lens every day to record my life, I realized how local my life was. No matter how I painted things that seemed meaningless, they were still full of Hong Kong flavor. At that time, I felt it was better to truly invest in doing this.”

He used to resist a bit whenever he heard others comment that his work was very “local”. Later, he discovered that living in this city, even a simple street, carries everyone’s shared experiences and memories, which is unavoidable. Perhaps it was fate, his “Hong Kong Street Series” and “Hong Kong Taxi Series” have become his highly representative works. To this day, he continues to constantly capture the same street corner scenery with his phone, believing that everything also holds different historical significance in different periods. Through his creations, he unintentionally became an observer and recorder of the city.

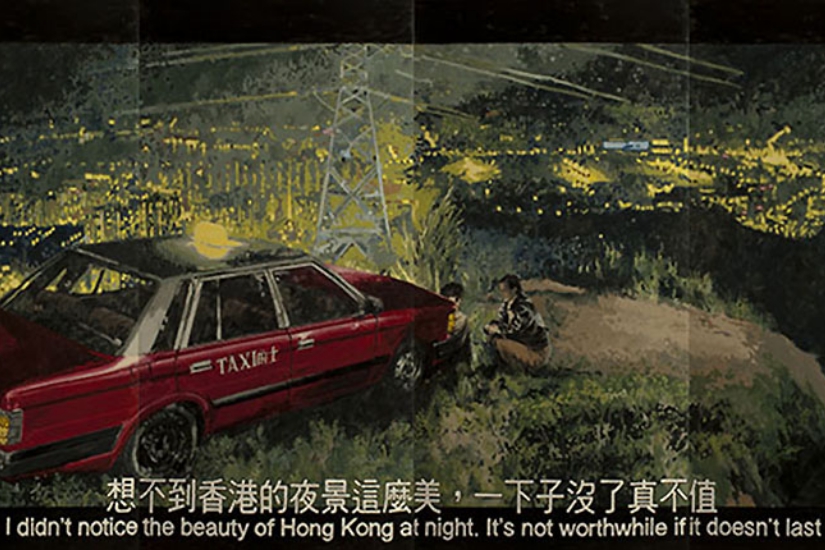

“The Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 1990s carry many nostalgic memories, as well as different people’s interpretations in the scenes. What I can appropriate is not just the visuals themselves, but the underlying meanings.”

Later, this practice of painting local culture and collective memory continued in another familiar series called “Film Painting Series.” Many of the works in this series are inspired by classic Hong Kong films. Chow Chun-fai mentioned that when he appropriates these works for his own creations, they take on a deeper meaning. He shared, “When a film becomes a painting, you can receive the initial message from the dialogue, but if you have seen the film and know the story, you can read into it more. So, for me, it’s a more free interpretation, but it still falls within a certain framework, which is why people resonate with it.” Like him, the works in the Film Series are free, yet based on a certain social context, allowing viewers to connect the messages from the films to current societal issues, triggering more emotional associations and evolving into a meaningful creation.

In the works of the film series, many are artists’ responses to social conditions. Sometimes the dialogues excerpted in the works are very direct, but if the audience does not understand the historical background and content of the film that generated the work, it is also possible that they will not understand what the work is trying to express. Is this kind of creation direct or subtle after all?

He said, “I try to achieve multiple layers, in simple terms, the drawings in the movie are direct. Multiple layers mean not just reading the thoughts on that painting from the dialogue, but understanding the background of the movie, art history, and elements of painting. Perhaps the kind of red I arrange in the painting has a different meaning for you, that kind of interpretation is not so direct, but more internal reflection.” For artists, even seemingly very rigid or rational creations can still bring out some spiritual essence.

He talked about his past work on the painting “A Better Tomorrow”: “This movie represents some of the Hong Kong people’s imaginations about the uncertain future. The English title of the film is ‘A Better Tomorrow,’ which contains the hopes of the people at that time for Hong Kong.” If we place the hopes and feelings that the director had in the film at that time into the current society, it is also relevant. Art and culture influence each generation, and it is this enduring cultural image and local emotions that continue to inspire Chow Chun-fai’s creations.

“Creation is very subtle, while politics is relatively direct.”

Sometimes art always gives others a “lofty” feeling, because most people feel that using a canvas to express concern for the city is circuitous and powerless. Zhou Junhui has also had this realization in the past, so he chose to be an artist who creates purely, tried to get involved in the system, and actively expressed opinions on cultural policies, artist rights, and other matters.

Zhou Junhui moved into a factory building in Fo Tan as early as 2001, but at that time, using factory buildings as art studios was still considered illegal. So he joined forces with creators from different sectors to establish the “Factory Artists Concern Group,” hoping to discuss with relevant departments to amend inappropriate industrial regulations. At that time, there were still many vacant factory buildings in society, but at the same time, many local artists actually lacked creative spaces. However, the emerging cultural industry did not comply with the factory usage regulations established in the 1950s and 1960s, so engaging in creative industries in factory buildings was considered illegal, let alone creating there.

He then took the initiative to organize a pressure group, hoping to fight for the legalization of art studios in industrial buildings. He said, “It’s not that we have special rights or privileges for creating, but in industrial areas, everyone is in production, it’s just that we’re not really producing goods, but producing culture. Whether it’s painting a picture or making music, it’s actually a form of production. At that time, I hoped to let different policy departments know that the definition of industry should change, and cultural industries are also a form of industry.”

Since then, a full-time creator has begun to establish a relationship with the political world. At that time, there were no artists active in the industrial area, and it was uncertain how long one could create there. This instability made him feel like a “nomad” without a fixed abode. After years of struggle, artists were able to legalize their creations in the industrial buildings, and Fo Tan gradually developed into the “Fo Tan Art Village,” becoming a representative creative base in the local art scene. Chau Chun Fai not only witnessed the changes in Fo Tan over the years but also became an important pioneer in this artistic community.

“Artists participating in politics is a form of performance art.”

With the aim of advocating for more rights for artists and improving the local art scene, Chow Chun-fai ran for the Legislative Council in 2012. Faced with a unique election framework, he knowingly did what he knew he shouldn’t, turning what he described as a “doomed to fail” election into more of a performance art piece.

He shared, “Of course, what I care most about is not whether running for office is a work of art, or if this can be turned into a performance. What I care most about is what meaning that campaign holds, and whether it can lead to something.” The uniqueness of painting lies in its ability to express without words, yet the artist who usually speaks through images found himself in heated debates with politicians on the election forum. He said, “Back then, I hoped to bring these relatively minor, non-mainstream cultural issues to the forefront.” As he wished, the overlooked cultural issues were brought to mainstream channels of communication. Despite losing the election, he returned to his creative work contentedly, realizing he hadn’t lost anything.

Since once held the dual identity of artist and politician, what are the similarities and differences between the two?

He replied, “There are some similarities between the two. Politics and art are both forms of expression, reflections on and reactions to the external environment, and even caring for others. Perhaps because of these similarities, I have concerns about society and politics.” Although using art to express political demands in a subtle and indirect way is not the most effective method, based on Zhou Junhui’s experience, he seems to have successfully demonstrated the flexibility of navigating between two conflicting identities.

“In the search for a balance between reason and emotion, more creativity will be sparked.”

Returning the original sentence as it is already in English: Return to art, Zhou Junhui’s works are not only full of traces of local elements but also imply his concern for social politics. Is it because of creation that he began to pay attention to society, or is it because of paying attention to society that he expresses it in the form of painting? Perhaps that kind of concern for the community, as well as the profound feelings for life, is the driving force behind his continuous creation.

Facing the changes in the current situation, Zhou Junhui frankly said: “For a quite long period of time in the past, due to social events, I had no intention of painting at all.” As he described, when the most dramatic things have happened in reality, it is difficult to arrange more surreal things in the work. The sense of powerlessness makes it easy for people to fall into an emotional whirlpool.

Later, in order to prevent this kind of emotion from engulfing him, he began to reflect the events in society truthfully in his works, without any subjective criticism, giving the audience the freedom to interpret the works. In the past, he would have minded the lack of tactful handling in his works, but when faced with such overwhelming emotions, recording truthfully instead became an outlet for emotions.

In the past, in order to avoid letting emotions dominate his creation, Zhou Junhui deliberately chose seemingly more rational creative themes like “movie series.” Later, he realized that there is actually no pure rational or pure emotional creation. He said, “Whether it’s the creator or even ordinary people, everyone is struggling between these two things, hoping to find a balance between the two, but never really achieving that balance. Instead, in the search for balance, new creations will continue to emerge.” Even if he doesn’t know if he will ever find that balance, the search itself is meaningful. He believes that so-called emotional creations do not need to be deliberately explored, just live truthfully, observe this city and the people around you, and that sincerity will come out of the work.

Until now, he still enjoys the pleasure brought to him by creation. For him, creators have a unique way of life, which he describes as a “watching from a distance but also participating” kind of “jumping in and out” state. His creations have always been closely linked to urban life, hence the resonance in his works. But he continues to reflect on himself, hoping to find a balance between politics, personal life, and artistic creation, so that his creations can continue to evolve amidst this reflection and tug-of-war.

From taking taxis, creating, to entering the political circle, all kinds of experiences have made Chow Chun-fai constantly navigate between the city, identity, creative themes, sensibility, and rationality. This state of detachment is not unstable, but reflects the resilience and adaptability that Hong Kong people have always possessed.

Creation is the artist’s response to life, and it is precisely because of his deep concern for the community that Zhou Junhui’s works have become an important chapter in local art.

Executive Producer: Angus Mok

Producer: Vicky Wai

Editor: Ruby Yiu

Videography: Anson Chan, Andy Lee

Photography: Anson Chan

Video Editor: Andy Lee

Designer: Edwina Chan

Special Thanks: Chow Chun Fai