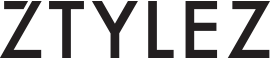

His stage play creations always exude a charm, drawing inspiration from classic literary works but constantly subverting them with fresh ideas. His works may be profound in concept, yet they leave a lasting impression. He is Edward Lam, a renowned stage director in Hong Kong. Since founding the “Edward Lam Dance Theatre” in 1991, he has produced over 60 theatrical works in the past 30 years. His works go beyond mere performances, serving as a key to enlighten the audience to explore themselves, reflect on the era, society, and how to navigate life.

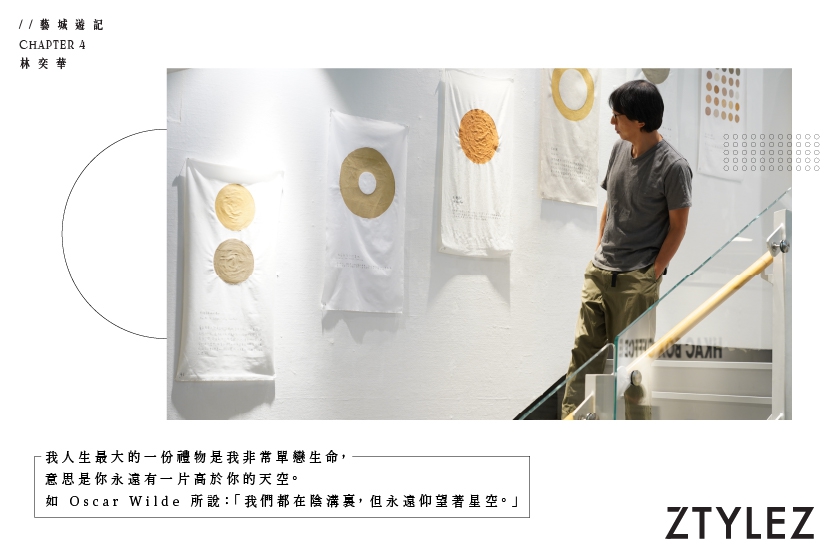

If creation is a lonely process, then producing a theater piece may be a relatively lively way. Each actor is busy running on the stage, coordinating with sound, lighting, props, body posture turning into lines, emotions rendering colors, making the stage present a story-like image like a canvas. However, after the applause, when the spotlight goes out, how do those directors who are used to observing in the shadows view each performance? For Lam Yik Wah, creating a stage play is actually painting, performance is a moving picture, and he is the one behind the brush. Joining the TV drama team at the age of 17, later studying abroad, establishing his own theater group, he admits that he tends to lean towards challenging difficulties. Stage play creation has never been mainstream, but for the cultural nourishment of a city, it is also indispensable.

This episode of “Art City Travelogue” invites director Lin Yihua to chat with us about his theater creation experience, allowing us to meet him outside the theater, listening carefully to how he leads the audience across space and time with his stage works, sparking more imagination about art and life.

“I don’t want the audience to see everything on stage, but rather to see a part, to imagine a part.”

Many people believe that appreciating a stage play is about watching the actors’ performances, but for Edward, he cares more about creating a larger imaginative space than just directing the play. He said, “The biggest difference between movies and stage plays is not just that movies have close-up shots, or can quickly switch time, because stage plays can also switch time with lighting, and the actors’ movements are the framing of a shot. The difference lies in how the stage director views ‘time’ as time, and ‘space’ as space.” While others hope the focus of the stage is on verbal expression, Edward has already transcended the framework itself, hoping to inspire the audience’s thinking. The stage space is no longer a limitation, but can provide the audience with a broader imaginative realm. He said, “I hope the stage that the audience sees is not just this big, but even bigger.”

Based on past experience in TV dramas, movies, and theater behind-the-scenes work, he jokingly refers to himself as a “stage director who films movies with a stage play approach.” Since he has been involved in different creative methods, we are all curious about which one he prefers. Edward mentioned that he used to think that film production emphasizes technical collaboration, while stage plays are more relaxed because everyone’s focus is on the distance between actors and the audience. However, with the advancement of technology, creating stage plays also involves dealing with lighting, stage design, and other issues. Directors cannot just focus on directing the play, but must also consider the overall presentation of the stage to provide the audience with the best visual experience. They even have to make them see from multiple senses, gradually realizing that the differences between the two methods are not actually that big.

However, Edward knows that the audience cannot absorb all the production information in this short one or two hours of visual storytelling. As long as the audience is sitting in the audience focusing on the actors’ performances, those moments are already perfect. Perhaps he cannot answer which expression he prefers more, because that is a pursuit of form. He hopes that viewers can empathize and understand themselves through the work, which is what he values.

“The core theme of my past works has always been about growth.”

Edward’s works include adaptations of classic works, as well as a wide range of topics such as urban modern life and interpersonal relationships. However, regardless of whether the works span ancient and modern times, tracing back to the source, they are all related to “growth.” Throughout life, we will always encounter many difficulties, and we slowly transform into a true “adult” through stages of hitting a wall, relearning, and changing. He shares with us that he enjoys interacting with students at school the most because they are not easily bound by existing thoughts. In the process of communication, he always gains inspiration from them. As an experienced director, he believes that he cannot let students feel that he is very authoritative. Only by breaking through the boundaries of identity and engaging with them can there be true exchange of ideas. It is precisely because he himself is someone who values communication from both sides, always showing curiosity and concern towards others, that he accumulates various creative inspirations in observation and communication.

However, inspiration is not something that can be found easily. Edward believes that creators need to first understand what they need, where their shortcomings lie, have empathy for others, in order to distinguish which inspirations and nutrients can be used for creation. He jokingly says that he still needs to continue growing, and this kind of direct communication with others allows each other to recognize themselves, or learn some essential qualities that they lack from others.

“I hope the audience can see themselves in the work the most.”

Looking back at past creations, many of them are adaptations of classic works, from “Dream of the Red Chamber,” “Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio,” “The Story of the Western Wing,” “Water Margin,” “Journey to the West,” “Madame White Snake,” and more. Edward is able to adapt works of different genres into stage plays. What is the most difficult part of bringing these classic stories to life in a theatrical form? He said, “From text to space, the most difficult part is to have the work converse with you, learning how to chat with the work is my biggest gain in the past.” His creations have never been about reshaping classics, but rather extracting the core ideas from the classics and extending these thoughts to the present. He said, “These texts have internal and external components, the external refers to the society and era at that time, the internal refers to emotions. Once you understand the emotions, it is not easy to be blocked by the clear walls that separate you from connecting with the text.” Therefore, he can compare “Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio” with the foreign film “Marriage Story,” regardless of East or West, regardless of era, certain emotions and human relationships are universally understood across generations.

Edward often challenges the ways of expressing time, space, and gender in his works, just like in the performance “Hello, Bao Yu” at West Kowloon in September. In the play, two actors perform together from a distance, and the audience can freely move around the theater space, subverting traditional performance modes and viewing experiences. Faced with such unconventional performance methods, not everyone may understand the cleverness and profound meaning of the work. For theater creators, whether the audience can understand the message of the play is a perennial question. What impact can their own work have on others?

He said, “It’s all about emotions. I hope the audience sees themselves, meaning I hope they have more reservations about themselves before entering the theater, so they can have more conversations with themselves afterwards.” He believes that although audiences may not admit it, deep down everyone wants to see themselves in the performance. He continued, “The surface layer is identification. Popular plays often show the audience their ideal selves, making them feel good about themselves. The second layer is when the audience sees their own problems and starts to think. The third layer is understanding the problem, accepting their flawed selves, and no longer seeking answers from others, but seeking a change.” Giving the audience the opportunity to rediscover themselves in a work is truly valuable.

“Every person’s life is limited, but creation can take him from one belief to another, one life to another.”

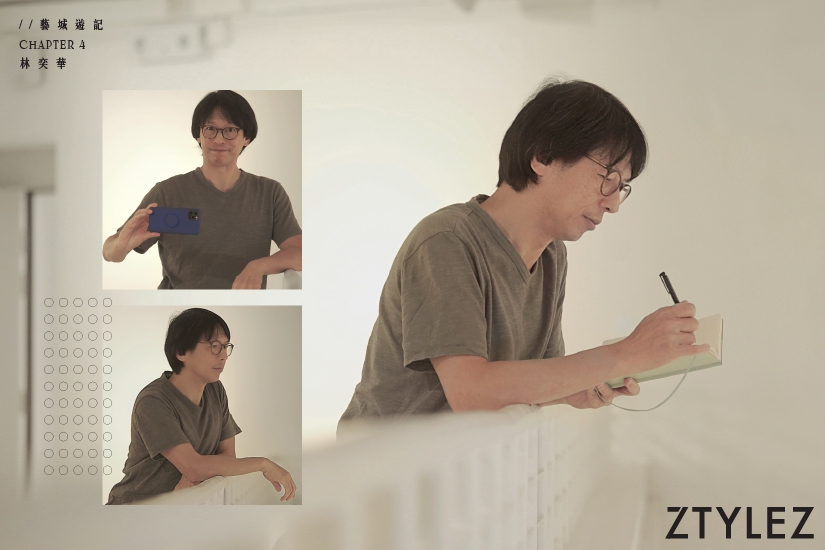

Theater performances allow space to extend infinitely, and so does belief. Perhaps it is precisely because of dissatisfaction with the present and hope for the future that Edward explores more possibilities through creation. He believes that unsatisfactory experiences are the greatest creative soil for artists. When we face various disappointments, pains, and loneliness in life, we construct imaginations of beauty, which then lead to creation. He feels that if life has never been disappointed and only encountered good things, those people may not become interesting artists. Love and pain always pervade everyone’s life, and we all use art to fill the void. Only when richness and desolation intertwine can life be complete.

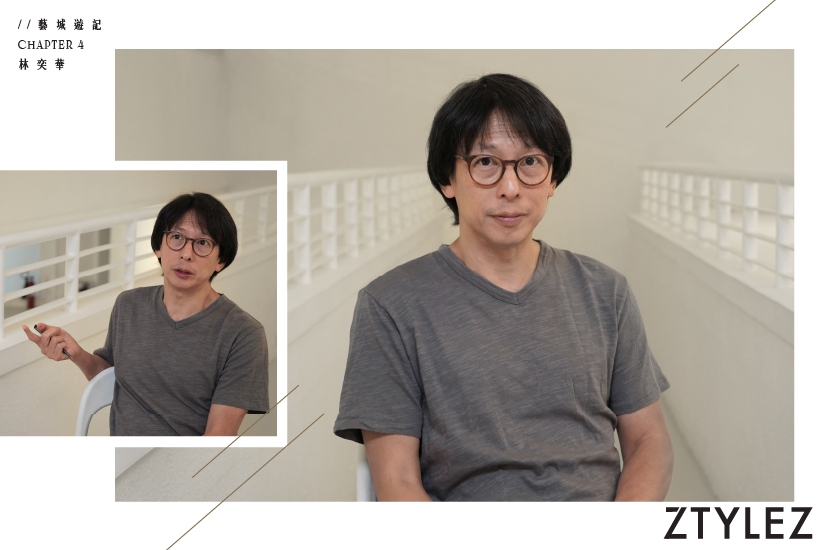

Edward also shared with us a unique theory of “unrequited life,” which is to approach everything with anticipation and admiration, and to always believe in a sky higher than oneself. He quoted a line from Wilde: “We are all in the gutter, but always looking up at the stars.” Edward said that his thirty years of creation have been influenced by different artists, even though their works are already ancient, the ideas and beliefs they carry will not fade with time, and now his stage creations actually continue those ideas.

“The stage is my home, the train station, I guess it will also be my grave.”

Since the establishment of the “Very Lin Yihua” theater troupe in 1991, there have been 64 theater works accumulated. Edward’s life has been closely related to the stage for decades, and the stage has long been his life’s belonging.

He said, “We often have misconceptions about death, with a great anxiety about the end point, feeling that everything ends at that point. But the value of creation lies in the fact that it does not impose limits as limits, and endings as endings. Just as Van Gogh has been gone for a long time, but when we see a certain shade of blue, we still think of him.” With creation, death is no longer frightening, because life continues forever through the works left behind.

Looking back on decades of stage experience, he said, “A work is a place where a person leaves traces from birth to departure. If I hadn’t been involved in the theater, the traces I leave behind now might not be what they are today. Recently, because of the theater company’s 30th anniversary, I opened up these works for a rewatch, and it was actually quite moving. I found that they can all be connected in a line, and what emerges is a map, and that map is Hong Kong.”

Having developed in other places in the past, his works have also been performed on stages in different locations. In the end, he chose to establish a theater company in the land that nurtured him, silently persevering for decades. Was it all out of love? What creative nutrients has this city given him?

Edward feels that Hong Kong has given him not only the ability to learn the language, but also inspiration from different cultures, and most importantly, opportunities in stage creation. If he had chosen to develop elsewhere in the beginning, he might not have achieved what he has in the past 30 years. However, he also admits to having a “love-hate” relationship with this city, recalling how he entered the TV industry at 17 as a scriptwriter, signed a contract at 18, and left at 19, thus ending his short-lived TV career because he realized he did not like the mainstream content. Returning to Hong Kong from the UK in the 90s, he found that the city had undergone drastic changes, with society being filled with materialism, gossip entertainment, and one-way education, which he could never comfortably accept. He said, “For the past 30 years, I have been doing one thing, which is not letting mainstream values define me, but understanding their relationship with myself, and then making choices.” However, he understands the difficulties of going against the mainstream, lamenting, “So you are destined not to be popular here, because you cannot embrace these values.”

Over the years, the “Very Lin Yihua” theater troupe has collaborated with artists and groups from different cities and media to explore new aspects of Chinese-language theater. Although the arts have never been mainstream in society, these 64 works undoubtedly have a significant impact on the cultural scene. How does the director himself view this stage of the theater troupe?

He said, “Too few people have seen it, too few people have seen these 60 or so works. This may not be a fact that I can change within my abilities, because from the establishment of the group to now, I have made more than 60 works. If someone is willing to watch them all, you can imagine that a lot has happened in them, all related to myself, to this place, recording how much I feel about this place. But for whom these events are meaningful, whether they have any meaning for the future, is not something I can decide. I can only be grateful that they have all happened, and that the things that have happened can be related to the times and people’s hearts. I feel that this is already a gift to myself and others in my life.” Regardless of practical considerations, being able to create works that touch people’s hearts is the greatest gift to the creator.

Thank you “Fei Chang Lin Yihua” for presenting us with these years of theater, allowing us to borrow a moment in a play to meet the creators on stage, crossing space and time, and imagining more about life. Without the appearance of these more than sixty works, today’s literary world may not be what it is now, but what has appeared will leave a mark. May the theater company have another 30 years in the future, allowing the director to continue to carve growth on the stage, and let each encounter cultivate an inexplicable fate.

Executive Producer: Angus Mok

Producer: Vicky Wai

Editor: Ruby Yiu

Videography: Andy Lee, Kenny Chu

Photography: Andy Lee, Kenny Chu

Video Editor: Andy Lee

Designer: Edwina Chan

Special Thanks: Edward Lam ; Hong Kong Arts Centre Venue Hire